War and Peace between Small States in the Age of Competitive Multipolarity

The Perils of Confrontational Multipolarity for Small States

The global political landscape has shifted from the relative stability and predictability of a US-led post-Cold War unipolar world order to a more complex and volatile multipolar system. The intensified, irrevocable tectonic transition from a post-Cold War unipolarity, characterised by a unified understanding of international politics and its inherent values, to an emergent, competitive, non-Western multipolar structure with counter-interpretations of the rules and norms of international relations may result in decades of global uncertainty. This definitive emergence of a volatile non-Western era, marked by its defiant challenge to West-entrenched norms of the liberal world order, is epitomised by Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine aimed at thwarting Euro-Atlantic integration, China’s military assertiveness in its eastern strategic peripheries to the detriment of Western influence, Azerbaijan’s expansionist war and ethnic cleansing policy against Armenia and Armenians, Turkey and Iran’s West-exclusive regionalism, and the augmented consolidation of autocracies through non-Western global institutions such as BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and the Organisation of Turkic States.

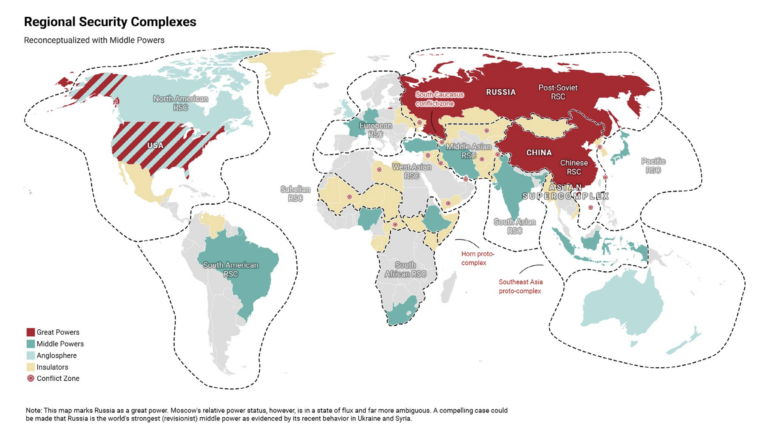

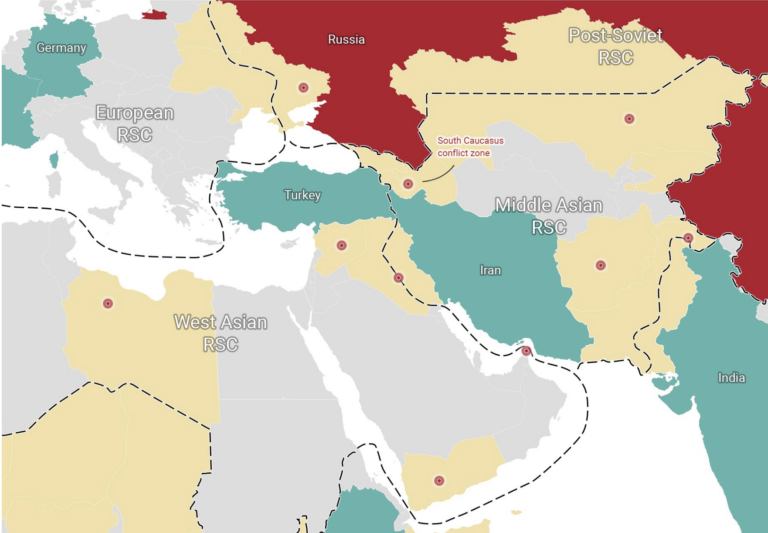

Institute for Peace & Diplomacy – Middle Powers in the Multipolar World, March 2022

This new era of global uncertainty, characterised by the competitive dynamics of several major powers, poses significant dangers for small states, where the relevant circumstances may permit different peers to contest their territorial integrity, sovereignty, and even existence. Historically, small states have found more security under unipolar and bipolar orders, where a clear hegemon or a balanced rivalry between two superpowers created a more predictable environment. In contrast, multipolarity introduces a higher degree of uncertainty and instability, which can be detrimental to the security and autonomy of small states. Under the unipolar world order led by the United States tentatively from 1991 to 2008, most small states obtained an opportunity to benefit from a liberal international system that promoted a standard set of pluralist and democratic rules, economic integration, and security guarantees, including the principle that the use of force in political disputes was unacceptable. The US and its allies acted as global agenda-setters, providing a relatively safe environment for small states to pursue their interests despite the dangers stemming from globalisation.

However, as the US’s hegemonic influence wanes, traditional and emerging powers like Russia, China, India, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, South Africa, Iran, Pakistan, and Brazil, among others, are vying to alter the West-centric liberal world order established during the period of uncontested unipolarity. These powers seek international recognition for their own agenda-setting efforts, aiming to organise their peripheries with distinct regional rule-making ambitions. The current stage of emergent assertive non-Western multipolarity could culminate in a situation in world politics where there are no commonly agreed codes of conduct, and many critical international norms are differently interpreted or contested by the competing poles. This power struggle leads to a fragmented international order with competing norms and values, destabilising smaller states caught in the crossfire.

In a bipolar system of the late 20th century, the clear division of power between two superpowers (the United States and Soviet Union) allowed small states located in strategic peripheries of bipolar ideological competition to navigate their foreign policies by aligning with one of the poles, or if lucky enough to stay neutral. The prerequisites of bipolarity often provided them with security assurances and strategic support emanating from the mutually deterring bipolar structure of the international system. During the stage of US-led unipolarity, small states in crucial geopolitical locations could leverage their position for favourable terms from the Euro-Atlantic and European communities. However, those on the periphery of the unipolar reach were more vulnerable, as they lacked the same level of strategic importance as the unipole and had relatively uneven terms for protection due to their strategic vicinity to the sources of transnational threats, such as terrorism, areas of lingering instability, or ineffective statecraft driven by their post-Communist regime transitions.

Overall, the multipolarity exacerbates the vulnerabilities of small states due to several factors:

- First, contesting multiple major Western and non-Western powers creates a more complex and fluid international system. Alliances are more volatile, and the lack of a single or dual stabilising force leads to greater unpredictability.

- Second, the multipolar systems often feature significant power imbalances, making deterrence more difficult. Stronger states can coerce or attack weaker ones without fearing immediate retribution from a balancing coalition.

- Third, the fluid nature of multipolar alliances and the shifting balance of power can lead to miscalculations about the resolve and capabilities of other states. The confrontational nature of the multipolar structure of global politics increases the risk of conflicts escalating beyond the initial scope of divergent powers.

- Fourth, local conflicts involving small states can draw in major powers, potentially escalating into broader confrontations. The interconnectedness of the multipolar world means that regional instability can have global repercussions.

The Tolerable Aggressiveness of Small States in a Competitive Multipolar World

Small states often face immediate security threats from neighbouring states rather than distant superpowers, a situation likely to be exacerbated by competitive multipolarity. This drives them to adopt offensive strategies to secure their interests and deter potential adversaries. Despite their relative lack of power, small states can become assertive and aggressive in a multipolar world, particularly when significant powers are preoccupied with their rivalries. The assumption that small states are inherently peaceful and defensive is misleading. Historical evidence shows that small states can be just as aggressive and expansionist as major powers, albeit within the constraints of their capabilities.

Several factors contribute to this phenomenon:

- First, in a multipolar system, significant powers may be less able to enforce order or intervene in minor conflicts due to their own strategic preoccupations. Such strategic negligence by major actors creates opportunities for small states to pursue aggressive policies with less fear of major power intervention. Since the major actors are in geopolitical rivalry, local wars between small states can be tolerated as the use of force by a small actor against another does not change the balance of power between the major actors, who may be preoccupied with more significant geopolitical engagements.

- Second, small states may have regional ambitions and seek to assert themselves as local agenda-setters or sub-hegemonic rule-makers, increasing their strategic value as regional players for the competing major poles. This situation can lead to conflicts with neighbouring small states as they attempt to expand their influence and impose new power configurations under their condition of new regional peace.

- Third, multipolarity offers small states more flexibility in choosing ad hoc alliance partners and manoeuvring diplomatically, seeking to exploit the ‘anarchic’ conditions of polycentrism to accumulate power and exercise it against a peer foe. Additionally, if smart enough, small states can play major powers off against each other, gaining support or neutrality from competing poles while pursuing their own assertive actions against peer adversaries, contributing to their isolation and defeat.

Institute for Peace & Diplomacy – Middle Powers in the Multipolar World, March 2022

Driven by its ambiguous conditions in terms of commonly accepted rules and unified world order, the inharmonious multipolar structure of international politics may tolerate the use of force by small states in different regional environments, where the use of force is an inherent part of regional norms and geopolitics. This may be possible for several reasons:

- First, major powers are often too occupied with their rivalries to respond decisively to conflicts involving small states. Such a circumstance reduces the likelihood of punitive actions or consolidated negative sanctions against the small state that applied military force and conducted an offensive campaign against the peer adversary.

- Second, disputes between small states usually have a limited impact on the overall balance of power among major actors. As a result, these conflicts attract less attention and intervention, especially from those major actors geographically distant from the region where the small states are involved in politico-military rivalry, or due to the multipolar competition with other peer-poles, the given region is no longer part of the order the given major power posited as a key stakeholder.

- Third, great or middle powers may tolerate or even support the actions of small states if they serve their strategic interests or if the small state’s aggression against another does not engender a situation that undermines their interests in terms of their multipolar rivalry. For example, a major power might back a small state’s aggression if it undermines a rival’s influence in the region.

Conclusion

The final transition stage from a West-centred post-Cold War unipolarity to a non-Western competitive multipolar world order presents challenges and opportunities for small states, especially those outside the European system. The instability and unpredictability of multipolarity increase the risks for these states, as the absence of a single rule enforcer leaves them more vulnerable to regional conflicts and power struggles. However, this lack of a single hegemonic power also gives small states greater autonomy and the chance to assert their interests more aggressively. This allows them to ‘fill the vacuum’ by positioning themselves as rule-makers in their immediate environments, provided they choose the right timing, consistently accumulate power, accurately assess their capabilities, and effectively bargain with potential stakeholders about the benefits of their own vision of regional order.

Contrary to the common perception that small states are inherently peaceful, they can be as assertive and belligerent as their larger counterparts, exploiting the fluidity of multipolarity to pursue aggressive policies and regional ambitions. The international community’s challenge is navigating this complex landscape and understanding the dynamics of a multipolar world where small states can play significant roles in regional order-making norm imposition, conflicts, and power shifts. Effective management of this new order requires recognising the dual nature of small states as both potential aggressors and victims of larger geopolitical rivalries. By mitigating the risks and harnessing the potential benefits of a more pluralistic global order, the international community can strive to achieve a more stable and balanced system of international relations.

Bibliography

Acharya, A., 2011. Norm Subsidiarity and Regional Orders: Sovereignty, Regionalism, and Rule-Making in the Third World. International Studies Quarterly, vol 55, p. 95–123.

Acharya, A., 2018. The End of American World Order. 2 ed. Cambridge: Polity.

Buzan, B., 2018. Polarity. В: P. Williams & M. Mcdonald, ред. Security Studies: an Introduction. 3 ed. London: Routledge, pp. 155-170.

Buzan, B. & Wæver, O., 2003. Regions and powers: The structure of international security. 1 ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Handel, M., 1990. Weak States in the International System. 2nd ed. London: Frank Cass Press.

Kassab, H. S., 2015. Weak States in International Relations Theory: The Cases of Armenia, St. Kitts and Nevis, Lebanon, and Cambodia. 1 ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mearsheimer, J., 2019. Bound to Fail: The Rise and Fall of the Liberal International Order. International Security, 43(4), p. 7–50.

Mearsheimer, J. J., 1998. Back to the Future: Instability in Europe after the Cold War. В: Theories of War and Peace. London: The MIT Press, pp. 3-54.

Pedi, R. & Wivel, A., 2022. What Future for Small States After Unipolarity? Strategic Opportunities and Challenges in the Post-American World Order. В: N. Græger, B. Heurlin, O. Wæver & A. Wivel, ed. Polarity in International Relations: Past, Present, Future. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 127-148.

Rickli, J.-M., 2008. European Small States’ Military Policies after the Cold War: From Territorial to Niche Strategies. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 21(3), pp. 307-325.

Rothstein, R. L., 1968. Alliances and Small Powers. London-New York: Columbia University Press.

Vital, D., 1971. The Survival of Small States: Studies in Small Power/Great Power Conflict. London: Oxford University Press.

Wallace, M., 1973. War and Rank Among Nations. Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books.

Wivel, A., 2023. Small States and the War in Ukraine. Transatlantic Policy Quarterly, 21(4), pp. 87-93.

Wohlforth, W. C., 1999. The Stability of a Unipolar World. International Security, 24(1), pp. 5-41.