Strong Sovereignty and Unity At Home: Armenians’ expectations from The Third Republic

7-minute read

As part of an ongoing engagement with the global Armenian community, Armagora.am, a project powered by The FUTURE ARMENIAN Foundation, continues an ambitious series of comprehensive public attitude assessments aimed at mapping Armenians’ views on the foundational challenges and opportunities facing the nation. One of the topics was the third Armenian Republic. It invites members of our community to express their expectations, hopes, desires and disappointments with Armenia’s third experiment with sovereignty, the country that exists today. As Armenia reels from the effects of the 2020 second Karabakh war, and the subsequent total loss of that ancient land-a calamity made ever more impactful by the massive refugee crisis it caused-Armenians, be they displaced from their homes in Artsakh, living in the Armenian republic, or spread out in one of the many diaspora communities across the planet, find themselves reassessing the successes and failures of our ancient state. While many paths have been suggested leading from an Armenia which survives to an Armenia which thrives, respondents have been unanimous about which directions these paths lead forward.

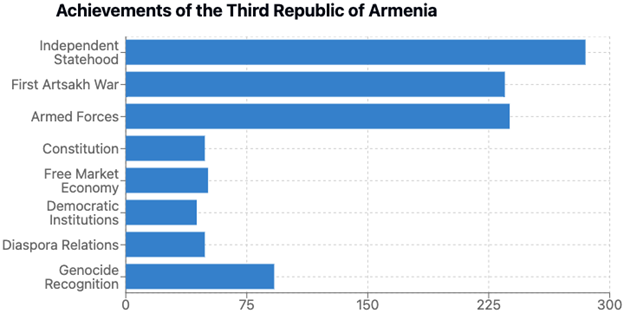

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the holy trifecta of modern Armenian identity: (re)achievement of Independence in 1991, compounded by the 1994 victory in Artsakh, and hinged on the establishment of an Armenian military in 1992, are issues beyond debate, with 72% of respondents citing these as among independent Armenia’s greatest achievements. This sentiment is echoed by philosopher and former parliamentarian and ambassador Ashot Voskanyan who believes that all these aforementioned achievements of the third republic are actually one and the same, and should be seen as the result of necessity. “There’s a reason that the Azerbaijanis and Georgians continue to celebrate the independence days of their first republics, since they see themselves as continuations of these states”, Voskanyan argues that Armenians, for their part, have placed a stronger emphasis on celebrating their second independence on September 21st because they see the third republic as as second try, rather than a continuation: an opportunity to learn from past mistakes, and “be ready”.

It’s not hard to see how achieving this hat trick of immense national victories immediately upon the formation of the third republic sets Armenia apart from its neighbors, as Voskanyan suggests, because while they attempted to seek continuity with their own grasps at sovereignty, Armenians were, in the 90s, looking to avoid the mistakes of their first attempt. Indeed, victory in Artsakh, under the conditions of deprivation, blockade and electrical disruption that it entailed, less than three years after achieving independence was so crucial to the revitalization of Armenian identity in the closing years of the 20th century specifically because it reversed a trend of Armenians being victims. It was “revenge” for the Armenian Genocide. Unlike in 1915, the Armenians of 1994 would not go quietly into the night; not without a fight.

As a side note though, the establishment of democratic institutions, free market economic models, or even the Constitution don’t seem to gather much excitement among poll respondents. This may perhaps be a result of these notions being considered to be self-evident by respondents, meaning that there was no question that an independent Armenia would be a liberal-democracy? It may alternatively suggest that most Armenian respondents simply didn’t care what sort of Armenia would come to bear, so long as Armenia were to exist.

Unsurprisingly, the inability to capitalise on this historic moment of national unity, and the eventual undoing of this victory in the form of Azerbaijan’s successful campaign of ethnic cleansing. This, along with the defeat in 2020s 44 Day War, are followed closely by the third most popular answer to the question “What are the biggest failures of the 3rd Republic?”: corruption and ineffective governance. Much like the top three responses to the first question, the most popular answers to the question about failure are also intimately interrelated, and speak to a failure of statesmanship deeply rooted at an institutional level.

While there is no surprise as to which three options would make it to the top three in terms of answer percentiles, it’s the order which raises eyebrows, particularly from Voskanyan. “Not that the war wasn’t an issue, because of course it was also a failure” Voskanyan notes, “But the war was the product of a failure to resolve the issue in the first place”. In here lies an argument about the procession of failures. While they say hindsight is twenty twenty, political analysts and historians still argue today as to what Armenia could or couldn’t have done to avoid war both in the immediate antebellum and from the onset. The issue always remains that in such “could have, should have, would have” scenarios, it’s easy to omit that the opponent also has a say on when wars take place. Regardless, this query still leads to another logical question, if war was inevitable, then why was Armenia not ready to fight it? These questions, as of yet, have no answers, though it is telling that they continue to be asked, by intellectuals, government policy makers and the Armenian public at large–both in Armenia and the Diaspora–as, much like the questions about the state’s triumphal independence, their answer will be foreboding how things come to be for the Armenian state and nation in the future. Quoting the words of the famous Armenian writer and politician Avetis Aharonyan, which Voskanyan alluded to earlier, “independence was knocking at our door, but we weren’t ready. Our task is to be ready”.

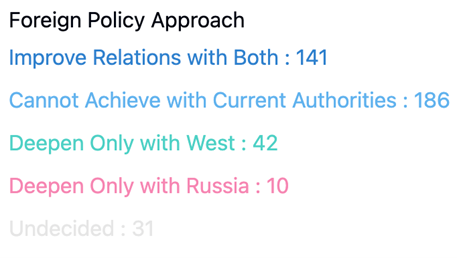

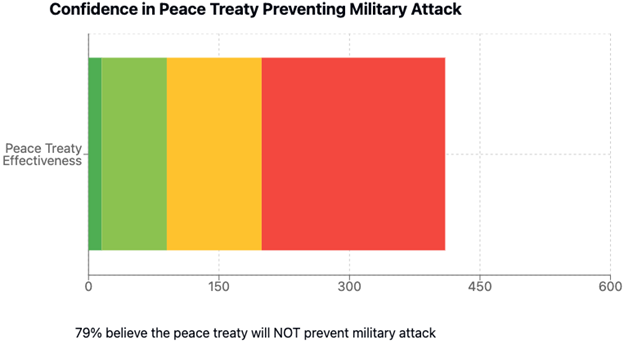

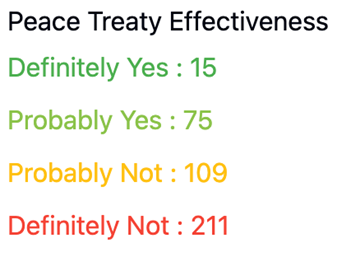

They forbode the future, since once again Armenia is rebuilding statehood: judicial reform, educational reform, military reform from the ground up, all spearheaded by a government which had virtually no experience in power as recently as five years ago. Once again an ancient nation finds itself with a nascent statehood. This “new” state yet again finds itself negotiating tenuous peace treaties with aggressive opponents, or rebalancing a delicate web of international alliances with ineffective old allies, and untested new friends. And yet again, respondents seem almost unanimous in their answers: A peace treaty with Azerbaijan is unlikely to lead to lasting peace, Russia is no longer a trustworthy partner, and inefficient management, coupled with violent overtures from Baku and a loss of identity are the top three greatest threats to Armenia. However, unlike the answer to question 1, feelings here seem much more evenly distributed.

In general though, this informal survey of public opinion makes clear that the establishment of the Armenian Republic remains firmly gripped in the Armenian psyche as a founding element of national pride. There is, despite bickering over trivial political matters, a broad consensus about what the problems were and what the solutions are going forward.