Despite concerns, Armenians see Nuclear as an integral part of the country’s future sustainable energy mix

7-minute read

As Armenia navigates an increasingly complex geopolitical landscape, understanding public sentiment on strategic issues has never been more crucial. This is why Armagora.am, a project powered by The Future Armenian Foundation, has launched an ambitious series of comprehensive public attitude assessments aimed at mapping Armenians’ views on the foundational challenges and opportunities facing the nation. Our latest poll, focusing on Armenia’s energy future, is part of this wider initiative to foster informed dialogue on issues central to Armenia’s development. In a region where energy security often intersects with national sovereignty, gauging public understanding and preferences around energy policy provides vital insights for policymakers and stakeholders alike. This poll, examining attitudes toward nuclear power, renewable energy, and international partnerships, represents just one component of our ongoing commitment to elevate public discourse around Armenia’s strategic priorities.

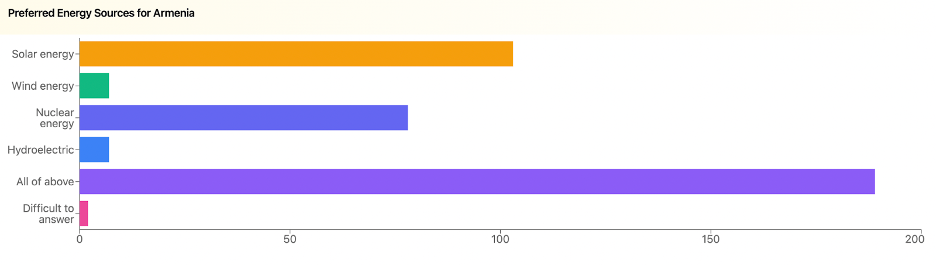

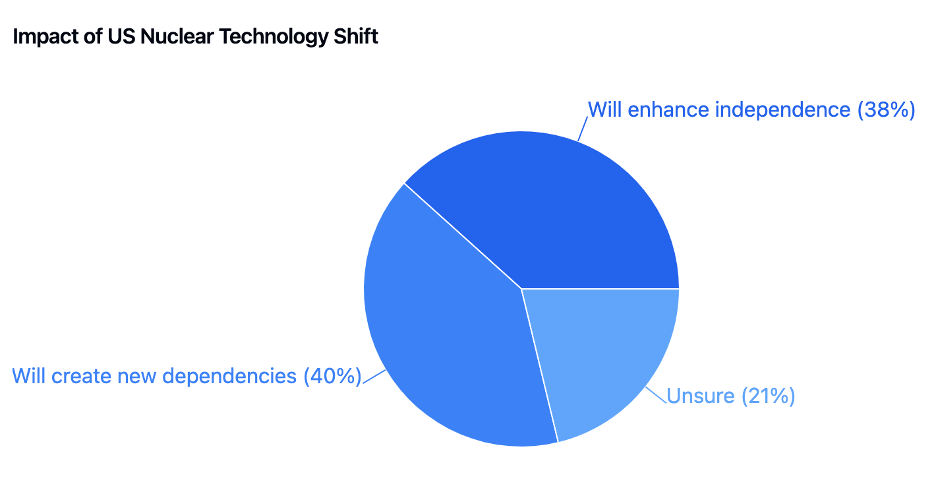

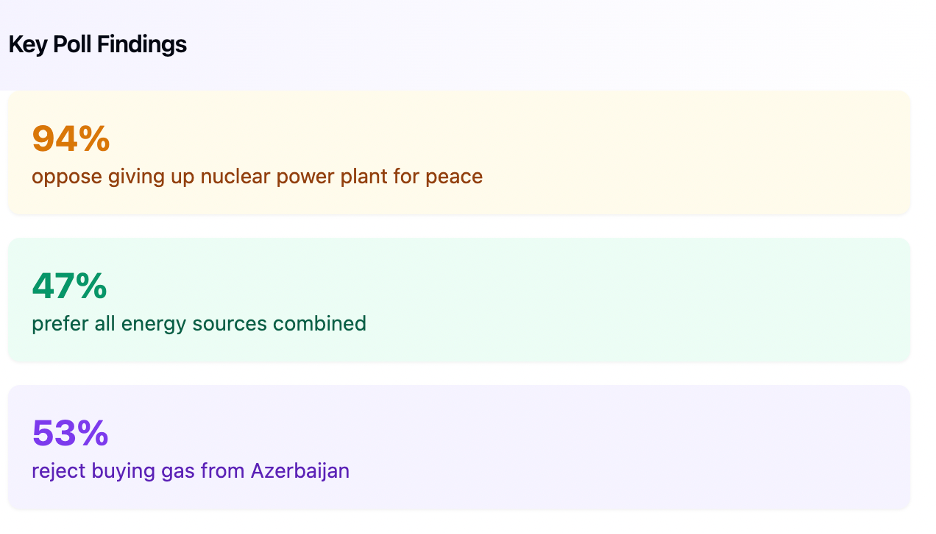

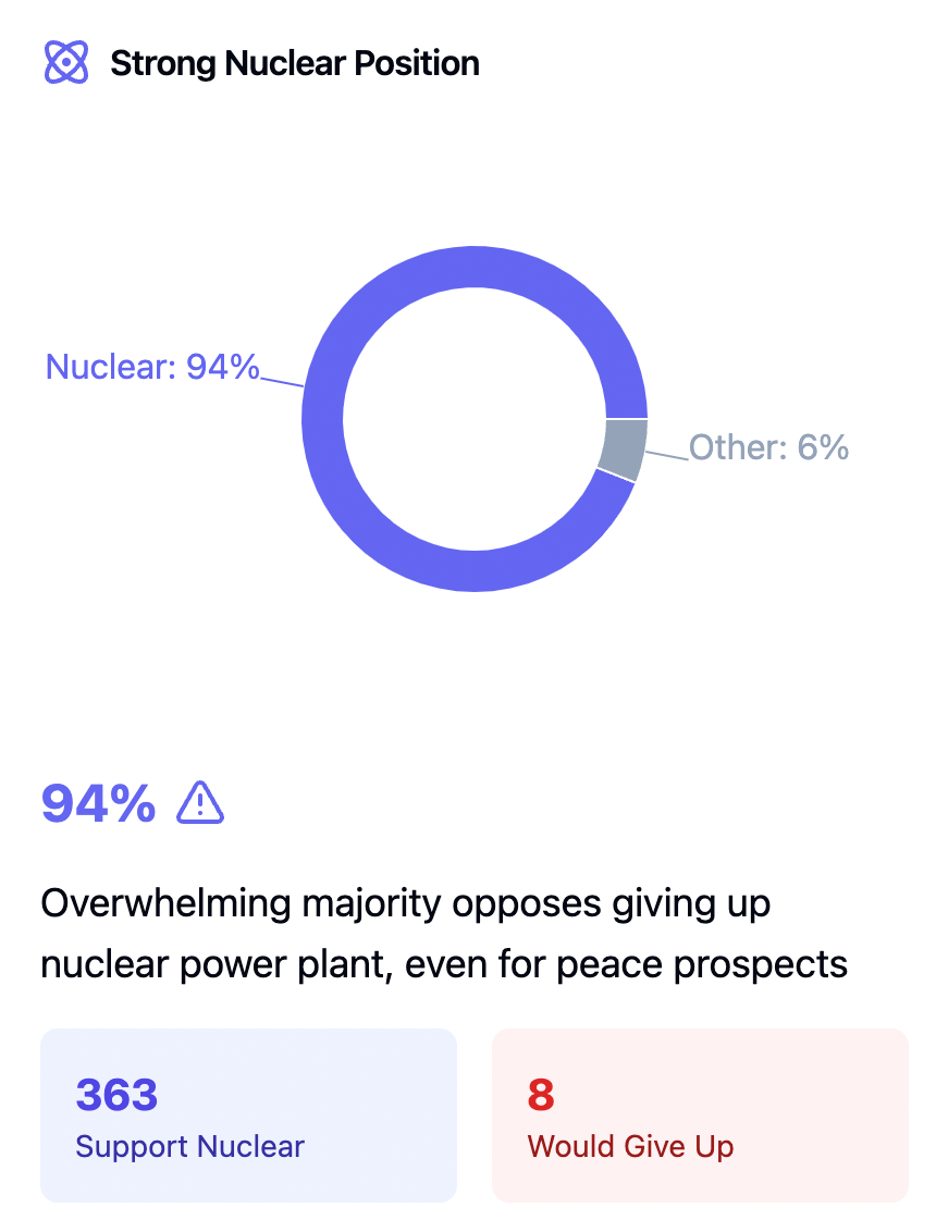

The poll of 386 voters reveals clear priorities for the country’s energy future. With 49 percent supporting a diverse energy portfolio and 27 percent specifically supporting solar power, there’s strong public backing for a mixed approach led by renewables. However, the most definitive finding is the near-unanimous support (94 percent) for maintaining nuclear capabilities regardless of political pressure. This commitment to nuclear power, combined with an even split on U.S. nuclear technology adoption (38.3 percent in favor, 40.4 percent against), provides a glimpse into the extraneously complicated geopolitics of nuclear energy–and energy relationships in general–that Armenia continues to navigate through.

The data reveals a fascinating picture of how Armenians view their country’s energy future. While they strongly favor renewable energy, particularly solar power, their views reflect a deeper understanding of Armenia’s unique position in a complex region. Solar energy emerged as the clear favorite among specific energy sources, a choice that makes practical sense given Armenia’s climate. But what’s more telling is how Armenians aren’t putting all their eggs in one basket. They see nuclear power as an essential part of the mix, highlighting a pragmatic approach to meeting the country’s energy needs.

When it comes to dealing with neighbours, Armenians show surprising flexibility. Despite historical tensions, most respondents in the poll claimed they would consider buying gas from Azerbaijan if it made economic sense. This suggests a population ready to separate “political grievances” from practical needs – though with clear limits. Yet those limits become crystal clear on one point: nuclear power. When asked if Armenia should give up its nuclear plant to secure peace with Azerbaijan, the answer was an overwhelming “no.” The message? Energy independence isn’t a bargaining chip.

This majority view is corroborated by physicist Areg Danagoulian, who teaches nuclear science and engineering at MIT. In a livestreamed “Ask Me Anything” session organized concurrently with the poll, Professor Danagoulian agreed with the need for a diverse energy mix, but stressed the importance of exploring the differing economic impact that each source of energy would have on the country.

That pragmatism once again reverberates with Dr. Danagoulian’s assessment. Reminding viewers that, technically Armenia sometimes already buys small amounts of Azerbaijani gas now, largely since Azeri and Russian gas sometimes mixes in transit through the Georgian gas pipeline network, the MIT professor stresses the need for a fail safe. “As much as we might not like it, we always need to have the maximum available number of options in case, for whatever reason, we hypothetically get cut off from the Russian gas network”, he told viewers during the AMA, arguing that the ability to buy gas from an undesirable source outweighs the potentially economy-toppling effects of sudden cut off from a single source.

Finding itself in the centre of an increasingly volatile region, Armenia is increasingly hard pressed to leverage what options it has at its disposal to develop a sustainable energy solution which would minimise vulnerability to external shocks, without compromising on the projected growth in energy demand as the Armenian economy continues to punch above its weight.

Energy Trilemma Index, which ranks the World’s countries by their ability to sustainably provide for their economy’s energy needs in three key metrics: security, equity and environmental sustainability, ranks Armenia as 58, globally. With no proven oil reserves (though some exploration licenses have been issued in recent years), Armenia has historically been hugely dependent on external sources of energy–particularly oil and gas–to meet its exponentially growing needs. Since even much of Armenia’s local electricity output is sourced from thermal plants, that production is beholden to outside natural gas imports.

Long a cause for celebration, and simultaneous concern, uncertainty surrounding the future of Armenia’s Metsamor nuclear power plant (NPP) remains a critical component of any energy independence strategy. Despite the lingering shadow of Chernobyl, and questions over the Metsamor NPP’s age, safety ratings, and cost, successive Armenian governments have continued to keep it running, and finance much-needed life extending upgrades, since, no viable alternative way to cover the 40 percent of Armenia’s energy mix has been explored; at least so far.

The NPP itself was designed and built between the late 1970s and early 1980s around the standard soviet VVER-440, modified with extra safety features to alleviate concern about Armenia’s position in a potential seismic zone. Those who still have the memory of the 2019 HBO historical thriller Chernobyl in their minds needn’t worry, as the VVER series of reactors are inherently safer than the RBMK reactor counterpart used in that ill-fated NPP, and constant modifications have helped extend the station’s life well into the 21st century.

Aside from the 40 percent of Armenia’s electricity production provided by the NPP the rest is primarily covered by hydroelectricity (consisting of two major power plants: the Hrazdan and Vorotan cascades) and then two thermal plants: the Hrazdan and Yerevan plants, which together supply just under a quarter. But, unsurprisingly to anyone who’s read the previous paragraph, thermal plants need gas, and Armenia doesn’t produce any domestically.

Respondents to the poll seem to favour renewables as a key area of focus, with 27 percent supporting Solar specifically, and the country’s leaders seemingly have listened. While Armenia has attempted to both diversity its energy mix and meet sustainable production targets with serious investments in renewables such as hydro, solar and wind (with Masrik 1, the largest solar plant in the region generating 128,332 GWh of electricity yearly, expected to come online this year), it’s not as simple as building more of that infrastructure. These solutions do little more than complement, rather than replace the combined 815 MW which Metsamor’s two reactors generate.

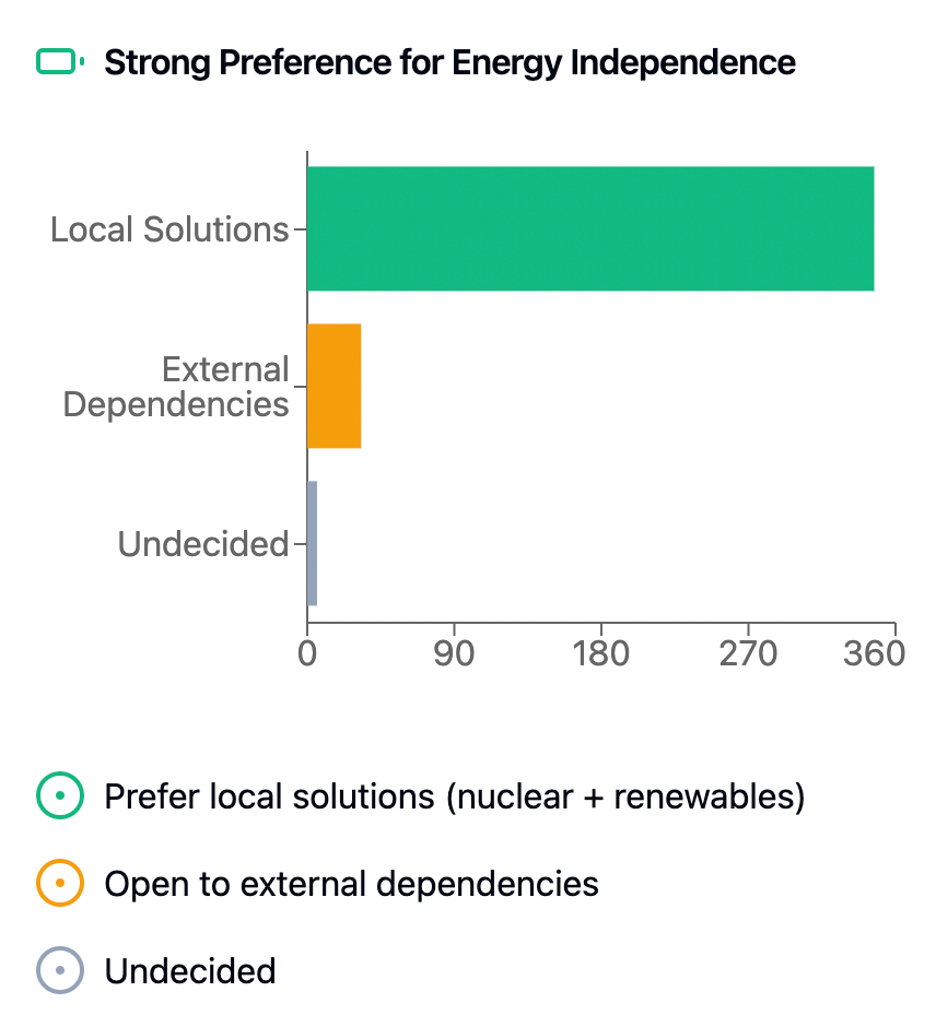

The deep-running desire that Armenians have for energy self sufficiency is quite obviously reflected in the polling data. Most respondents (to the tune of just under half) want Armenia to focus on developing local renewable resources rather than relying on foreign sources. They’re also open to new partnerships, showing particular interest in switching from Russian to US nuclear technology. This isn’t just about energy – it’s about reducing dependency on any single ally, especially Russia.

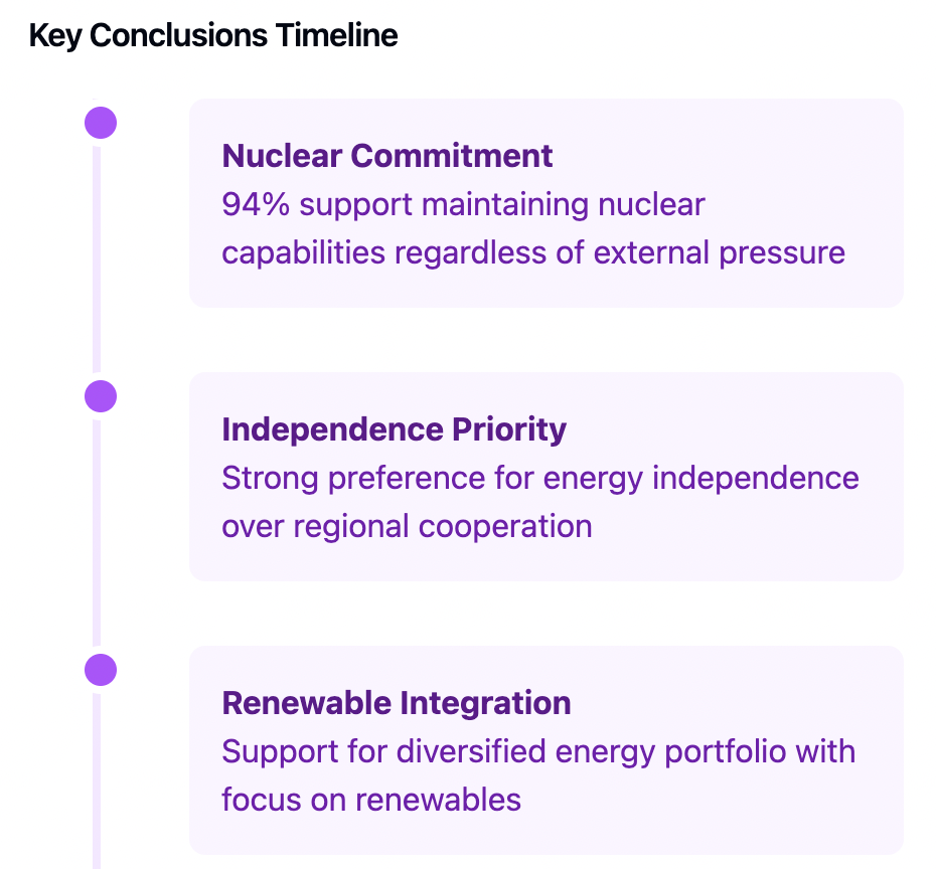

What emerges is a vision of Armenia’s energy future that’s both ambitious and practical. Armenians want to harness their country’s natural advantages in solar power while maintaining the stability that nuclear energy provides. They’re willing to work with neighbors and new partners, but not at the cost of energy independence. This balanced approach suggests a sophisticated public understanding of Armenia’s energy challenges. People recognize that in a region where energy often doubles as a political tool, the best strategy combines sustainable local sources with reliable baseload power and carefully chosen international partnerships.The data points to three key recommendations for Armenia’s decision-makers to focus energies on: First, prioritise solar power development while maintaining nuclear capacity as a backbone of energy security. Second, focus on domestic energy production, since other options such as a hypothetical energy cooperation with Azerbaijan remain distinctly controversial. Finally, launch a public engagement campaign to address concerns about international technological partnerships, as the significant uncertainty (21.2 percentage) regarding U.S. nuclear technology indicates an information gap which most Armenians could recognise from the constantly contradictory news and updates about the future of the Metsamor NPP. Taking these actions would deliver what the public wants: a secure energy future under Armenia’s control.

The willingness to consider pragmatic energy partnerships while maintaining clear red lines around strategic assets indicates support for what might be called “strategic pragmatism” in energy policy. This nuanced position – supporting both renewable development and nuclear maintenance – suggests Armenians expect their government to protect core national interests while remaining open to practical solutions. In essence, Armenians appear to understand what energy policy experts have long argued: that true sovereignty in the 21st century requires not just political independence, but energy autonomy. The poll paints a picture of a population that wants it all: clean energy, self-sufficiency, and strategic flexibility. And given Armenia’s position – a small nation in a complicated neighborhood – that might be exactly what it needs.